-40%

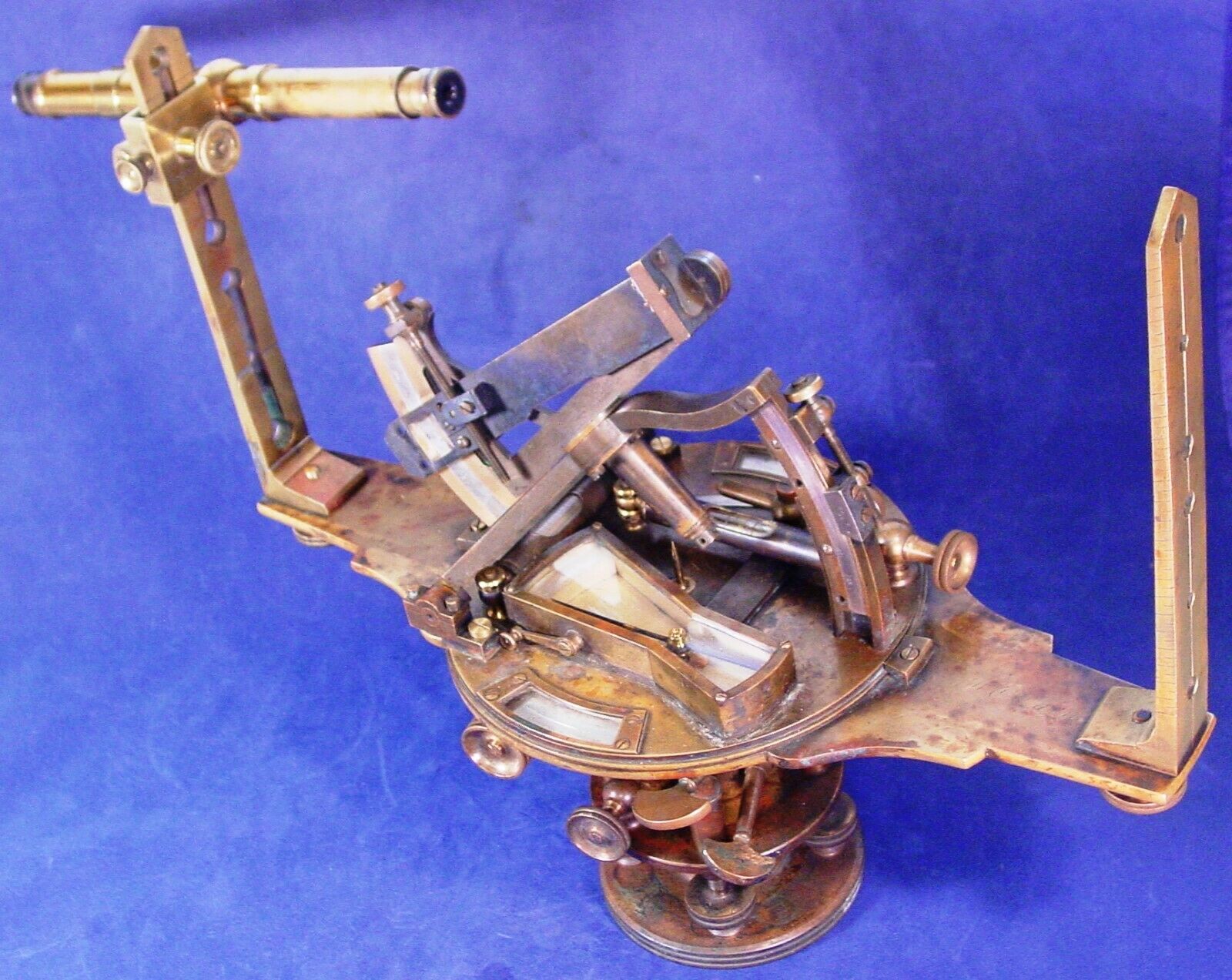

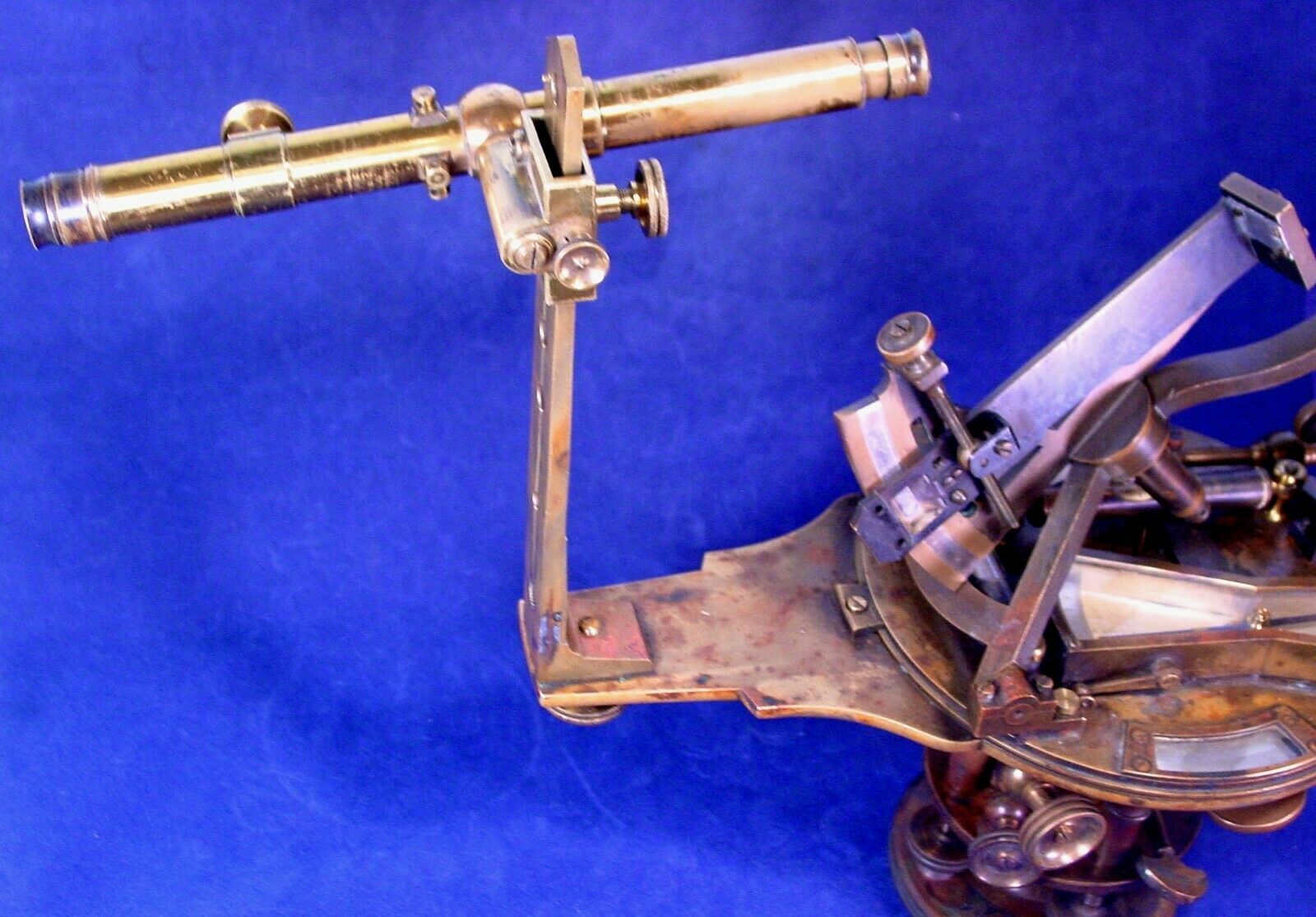

1880 Gurley Solar Compass with AMAZING Wyoming HIstory, W.O. Owen GLO Surveyor

$ 8448

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

This is an amazing solar compass instrument and the only one with the original owners name engraved into it known to exist.It is in great original condition, the motions turn well and it has a great patina.

It comes with a solar compass box, some extra solar components and a nice extension leg tripod.

The original owner was a rather famous General Land Office contractor surveyor in Wyoming, I have an extensive history of him below.

Serial number

None

Angular precision

1 minute

Length

14 ½ inches

Compass needle

3 ¼ inches

Plate diameter

5 ¾ inches

Postage is .00 if within the US, more If you are outside the US; no charge for careful packing.

Here is some information on the very colorful original owner, Billy Owens:

William O. Owen – U.S. Deputy Surveyor

William

Octavius

Owen

(1859–1947)

“Billy” grew up to be a small man, only five feet tall, which is perhaps why people called him Billy all his life.

He made up for his size with fierce energy and ambition;

he became Wyoming’s best-known surveyor.

He loved the work, both the math and the hiking.

Billy

moved to Laramie, Wyoming from Utah by emigrant wagon train with his mother and 2 sisters in 1868

.

Wyoming was actually part of Dakota Territory at that time. With the territorial capital being in Yankton, 500 miles distant, Laramie was a lawless railroad tent city.

In about 1869 or '70, Billy met two gentlemen with whom he would become intimately acquainted. These two engineers, pioneers and government surveyors were Mortimer N. Grant and William O. Downey. Mortimer Grant was a cousin of General Ulysses S. Grant. These two gentlemen were in business together and were city surveyors for the town of Laramie, county surveyors and US Deputy Surveyors.

From that day onward Billy Owen would have the direction of his life set. In 1873, Billy became an assistant on the crew of William Downey. He worked and went to school and in 1878 qualified as a civil engineer. His first survey contract as US Deputy Surveyor was for contract No.136 issued Sept. 20, 1881, and his last was contract No. 250 issued Sept. 2, 1891. This contract covered most of the Snake River and the valley around Jackson Hole to the west boundary of Wyoming.

Billy had many differing positions as a surveyor, he was county surveyor for Albany County, US Examiner of Surveys for the Department of Interior until his retirement in 1914, he was appointed US Mineral Surveyor for Wyoming in 1880 and executed many of the Mineral Surveys in the Medicine Bow and Hartville areas. He was elected State Auditor for Wyoming in 1894 and served for 4 years beginning Jan. 7, 1895.

Billy was the first to tour Yellowstone National Park, by bicycle, in 1883. On July 29, 1878 while surveying with William Downey in the Medicine Bow range, the crew ascended Medicine Bow peak and observed a total eclipse of the sun. This latter point serves to illustrate the knowledge these early surveyors had of astronomy and mathematics. Billy was of the first group to ascend the Grand Teton on August 11, 1898

which at 13,775 feet is the highest peak in the

Teton Range.

In 1891 and again in 1897, Owen made attempts to reach the summit Grand Teton, and was nearly killed on the second attempt. In 1898, a party of six sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Club managed to get four climbers to the summit on August 11th of that year. Though Owen was the organizer of the group,

Franklin Spencer Spalding

was the more experienced climber and was the first man on the summit. With Owen and Spalding were local ranchers Frank Petersen and John Shive. Petersen had been with Owen in their attempt in 1897. One day after their successful ascent, Spalding, Petersen and Shive climbed Grand Teton again to erect a rock cairn at the summit.

In 1927 the US Geographic Board named the second highest peak in the Teton range "Mount Owen" in recognition of Billy's climb.

The mountain was not climbed after Spalding-Owen climb for another twenty-five years until 1923.

Stones and “Bones” Set by William (Billy) Octavius Owen in Wyoming

By J.D. “Sam” Drucker

In November 2000, while helping to create the BLM’s geographic information system (GIS) base layer, termed the Geographic Coordinate Data Base (GCDB), I stumbled upon a General Land Office survey plat that fascinated me. It was drawn from work conducted by William (Billy) O. Owen in March and April of 1881 in southern Wyoming.

Cast of a fossil used as a marker. (BLM)

Noted on the plat is a line of section corner monuments labeled as “Mastodon Bones.” The idea of relocating and collecting some of these “bone” section corners was intriguing. I mentioned my intent to John Lee (cadastral chief, Wyoming State Office) and learned that his staff had first brought the idea to paleontologist Laurie Bryant in 1999. I soon realized that finding these corners was also interesting to others within the BLM.

Through research at the Albany County Courthouse, we found that some of the fossil corners did, in fact, monument the location of federal lands. Dr. Danny Walker, the assistant state archaeologist, suggested that we contact Brent Breithaupt of the University of Wyoming’s (UW’s) Geological Museum for information concerning the history and the types of fossils discovered in the survey area. Breithaupt introduced the potential for finding not mastodon, but dinosaur fossils, and excitement for the project grew. Beth Southwell, Breithaupt’s assistant, began preliminary research in the American Heritage Center on the UW campus and located a partial autobiography written by William O. Owen (Owen 1930) that made reference to the survey of the area and described what happened early in April 1881:

We had our team and wagon with us, and it was our custom, when possible, to load in the necessary number of stones at any favorable place and haul them along with us against the frequent happening that no corner material could be found when we have to have it. There was no sign of a stone near our corner point so I ran on north half a mile hoping to find a supply near the quarter-section corner. But in this we were disappointed. . . . Tom Hale, my old side-partner, was my cornerman and in our extremity he pointed to the east where, about half a mile distant, lay two hillocks where, in his opinion, might repose the material we needed.

Two of the boys jumped into the wagon and off they set for the hillocks. . . . After some time they started back and as they drew near I could tell they had considerable of a load. . . . ‘We’ve got something,’ said Tom, ‘but God knows what it is - I don’t. It’s harder then h___ and every piece weighs a ton!’ Now, what do you suppose those boys had in that wagon? Fossil bones of a dinosaur!

Upon reading this, the anticipation of discovery buzzed in the office, and soon a date was set for our long-awaited field trip. After acquiring GCDB coordinates for selected corner locations and inputting them into a hand-held global positioning system (GPS) unit, we began preparing for the field work.

On May 31, 2001, Lee, Mike Whitmore, and I, from the BLM cadastral staff, BLM paleontologist Dale Hanson, and Marty Griffith, from the BLM Wyoming State Office, set off for a day of investigation. Breithaupt and Southwell joined us in Laramie. We visited the site of the Bone Cabin Quarry to give us an idea of the type of material that Owen’s crew probably collected for corner material.

Our search began at the closing corner on the north boundary of the township. Whitmore was the first to see the corner stone, and almost in a daze of exhilaration, we photographed and chattered ecstatically about the piece of Sauropod fossil leg bone situated in a fence line. Sauropods were very large, plant-eating dinosaurs. The Apatosaurus (formerly known as the Brontosaurus) is one of the best-known sauropod dinosaurs.

Following our projected section lines and using GPS coordinates, we continued our search for one-half mile south of this corner stone and found the next quarter-section corner. This position had been monumented with a portion of a large fossilized Apatosaurus tail vertebra that, to our amazement, was plainly marked with “1/4” on the upper right corner. Owen had stated that these stones were too hard to scribe, so finding one that was marked only added to the historical significance of the original survey. It is possible that we were the first people to see this particular monument in 120 years. This fossil corner was collected and replaced with a BLM brass cap. It is currently housed at UW. Although we located several more bone monuments, there are several more we have yet to locate.

As we gather more information on the life and times of Owen, it seems fitting to call him a long-lost friend and comrade, a surveyor from the past, but one we all feel akin to. His accounts of surveying the high plains, deserts, and mountains of Wyoming convey the enthusiasm Billy must have had for life, his work, and adventure.

A Kid in Hell on Wheels

Laramie as the Railroad Arrived

By TOM REA

Billy Owen never saw a railroad until he was eight years old. His mother had told him about railroads. But in his mind as he traveled east by wagon train across Wyoming in the spring of 1868, he had imagined railroad wheels that looked something like wagon wheels. They rolled in grooves. Each groove was made by two rails. That meant it took four rails, as he imagined it, to make a track.

Sixty-two years later, when he sat down to write the story of his life, Billy (right, as a teenager) still recalled his amazement when their wagon rolled across the railroad tracks and into the brand-new town of Laramie. Somehow, the cars could run on just two rails! His mother explained to him that the steel railroad wheels had rims to keep the engine and cars on the tracks. Still, he wasn’t satisfied until he saw a train for himself—the engine with the big wheels, the cowcatcher on the front, the smokestack coughing sparks and wood smoke, the tender behind it full of firewood, the windowed cars the people rode in, and the box cars the things rode in all following obediently along. As the train pulled to a stop, the steam hissed, the brass bell clanged, and the big whistle let out a loud, shrill scream.

When they arrived in Laramie, the Owens ended a difficult family journey that had begun in England long before. Billy’s parents had lived near Bristol, on the west coast of England. They were married in 1852, and Billy’s older sister Eva was born a year later. By this time, many Mormon missionaries from the Salt Lake Valley of Utah were spreading the word of their new faith in England. The Mormons—members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—had first arrived in Utah in 1847. There they could practice their religion free from trouble, and the new church grew fast.

In England, Billy’s father, his mother’s brother, and his mother’s parents all joined the church. In 1854 Billy’s parents and his sister Eva, just six months old, made the long trip by steamboat to New Orleans, up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers by riverboat, and finally overland by wagon train all the way to Utah. Billy’s mother, however, had never joined the church. When they got to Utah, she discovered to her surprise that many Mormon men had more than one wife. This made her deeply angry, and though her husband and nearly all her neighbors in Pleasant Grove, Utah, were Mormons, she never would join. Billy’s second sister, Etta, was born in 1856. Billy’s mothers’ parents and his uncle Jim arrived in Utah in the late 1850s. Billy, the youngest, was born in 1859.

In spite of his wife’s feelings, Billy’s father remained a loyal Mormon and became an important man in the church. Finally, Billy's mother told her husband he must choose her or the church. He chose the church, and went back to England as a missionary. This made it very hard for the Owens. For three years, Billy’s mother and Eva moved to Boise, Idaho, where there were new gold mines. They ran a restaurant for the miners and had a little store. Billy and his sister Etta stayed in Utah with their grandparents, and went to a school run by the Episcopal Church—one of the few non-Mormon schools in the entire valley. Billy’s mother and Eva worked hard, saved money, and finally returned to Utah in 1866. But again, she decided Utah was not the place for the Owens. This time, however, she had enough money to take all her children with her. In May of 1868, she bought places for Eva, Etta, Billy, and herself on a wagon train headed east, toward Wyoming.

Billy and his family arrived in Laramie on June 14, 1868, after a trip of three weeks and 450 miles. The town was brand new, and the railroad had made it happen. The transcontinental railroad was building west across Wyoming. In early May, the tracks had reached Laramie. With them came thousands of workers, and hundreds of gamblers, prostitutes, and criminals skilled at separating the workers from their pay. Quite suddenly, Laramie was a town of 1,000 people, most of them living in tents. It had almost no government. Such towns were known as the End of Tracks or, more often, Hell on Wheels. A newspaper, the

Frontier Index

, kept its printing press and offices in a railroad car, as it had to move so often to the next End of Tracks.

Two companies built the transcontinental railroad. Mostly Chinese workers built the Central Pacific Railroad east from Sacramento, California. The Union Pacific (below) was built west from Omaha, Nebraska, mostly by Irish workers, along with many veterans of the Union and Confederate armies.

Each company was racing to get as far as it could across the continent before it met the other. To encourage the companies to take on such a huge job, the federal government gave them enormous tracts of land on both sides of the track, and paid them a certain amount per mile once the tracks were built and approved. This meant that the more track they laid, the more government money the railroads could claim. It also meant the railroads were built sloppily—with wobbly bridges, ties not well anchored in the ground, and rails that moved around too much as the trains ran over them. Accidents happened often. But the men who owned the railroads figured those problems could be fixed up later. The main thing now was to build the railroad

Near the end of 1866, the Union Pacific tracks reached North Platte, Nebraska. The next summer, Hell on Wheels was at Julesberg, in the northeast corner of Colorado—the same Julesberg that the Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota tribes had raided just two years earlier. Julesberg may have been the wildest of all the Hell on Wheels towns. One night, railroad construction boss Jack Casement and around 200 railroad workers felt they had to kill a number of gamblers. Things calmed down after that. By the end of 1867, the tracks had reached Cheyenne. In the spring, the tracks continued over the mountains to the west, and reached Laramie in early May, five weeks before the Owens did.

Billy’s mother rented some rooms in a hotel on what’s now First Street in Laramie, facing the tracks. Soon she opened a restaurant and store, just as she had in Idaho. Eva and Etta, by then 15 and 12 years old, helped their mother a great deal. (Owen-Nelson, 1938, p. 4) There were plenty of respectable people in town, Billy remembered 62 years later when he wrote an autobiography. There were also plenty of “bar room bums, thugs, garroters [that is, stranglers], holdups, thieves and murderers from railroad towns to the eastward, and the doings of this mob of criminals form a thrilling page in the history of Laramie.” (Owen autobiography typescript, p. 4) Thrilling, perhaps, when a person thinks back on it. But it must have been pretty terrifying to an eight-year-old boy.

Across the street from the Owens’ restaurant was a tent nearly half a football field long, taking up an entire city lot . It had a wooden floor, for dancing, and long bar down the right-hand side as a person entered.

Gambling tables took up the rest of the space. A band played full time. There were 20 or 30 women whose job it was to dance with the railroad men, and then lead them to the bar afterwards so they would buy expensive drinks. Most of these women were also prostitutes. Gambling and dancing went on all night. All his life Billy would remember the Keno dealer yelling, “Keno is correct!” and the square dance caller yelling “Promenade to the bar!” after each dance.

One day that summer, Billy was watching through the window when suddenly a crowd of men and women rushed out of the tent into the street. A man ran from the crowd, chased by a second man, carrying a pistol. The first was in the middle of the street when the second shot him, and “dropped him in his tracks,” Billy remembered. The crowd carried the injured man to an upstairs room, where he died soon. Ten minutes later the street was clear of the people, and the music, dancing and gambling going again full blast.

A city government was formed briefly that spring, but it soon fell apart. There was no Wyoming yet. Cheyenne and Laramie were still part of Dakota Territory, with its capital at Yankton, 450 miles away.

By late summer, people were being robbed in broad daylight and the criminals were pretty much running the town. At the same time, the End of Tracks had moved to towns further west. Laramie’s “better element,” as Billy called it, was growing, and these people decided things had gotten bad enough. They organized a vigilance committee—a committee of vigilantes ready to take the law into their own hands. In late August they hanged a man Billy remembered only as “the Kid,”—but that only increased bad feelings in town and didn’t stop the crime.

In October, the vigilantes raided the homes of three men—Asa Moore, Con Wagner (or Wager, or Wagan)

and Ed “Big Ned” Wilson, shot them full of bullets, and then hanged their bodies from the end of a log building downtown (right). The same night, they told a number of other toughs to leave town immediately or face the same treatment. Next morning, Billy and his pals got a long look at the bodies. They recognized Moore by his big red flannel neckerchief.

Later the same day, Billy and his friend Phil Bath were in the street when they saw a group of men come out of a saloon, one carrying a coil of rope. In the middle of the bunch was a man known to all as “Long Steve”—one of the men who’d been warned the night before. He hadn’t left town. They took him to a telegraph pole near the corner of what are now Grand Avenue and First Street, by the tracks, and hanged him from the cross arm of the pole. A big crowd had gathered. Phil and Billy watched from 20 feet away. His sister Eva watched from further back in the crowd.

That Billy would remember these events six decades later as “thrilling,” and not horrifying, as we might like to think they were to an eight-year-old, says something important about Billy and his times. He had a mostly ungoverned boyhood. He roamed the streets playing pranks with his friends. He roamed the creeks fishing and the prairies hunting with the same friends. They hunted with an antiquated black-powder musket out of which they would shoot gravel and nails when they ran out of bullets. Perhaps Billy’s mother and sisters were too busy running the business to pay him much attention. Or perhaps most boys’ families let them run wild, figuring they would learn important things as they did so. Billy certainly did.

As for Laramie, it got safer after the vigilance committee finished up its work, Billy remembered. Soon a real city government was established. Wyoming officially became a territory that summer of 1868, but no federal officials arrived to run it—no real law—until the following spring.

Meanwhile other towns along the tracks felt they had to use the same tactics. Three men were lynched in Dale City, a construction camp west of Cheyenne, in January 1868. In March, two more were lynched in Cheyenne itself. Then the four in Laramie, and in October, not long after the Laramie lynchings, five men were lynched in Bear River City, later called Evanston, in Wyoming’s southwest corner.

In 1894, he was elected state auditor, one of the five top elected officials in Wyoming. He lived most of his life in Laramie. After he retired he moved to California, but continued to spend his summers in Jackson Hole.

He and his wife, Emma, never had children. She weighed 250 pounds, and loved to bake him cakes. Billy’s great niece, Alice Downey Nelson, remembered him years later as a smart, fussy man with a short temper and a long, clear memory, who loved to tell stories.

Here is some information on the firm of W. & L.E. Gurley:

W. & L. E. Gurley

Troy, New York

William Gurley (1821–1887)

graduated as a civil engineer from

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

After going as far west as Michigan seeking employment as an engineer and finding none, he returned to Troy and went to work for five years as a foreman for Oscar Hanks, a surveying instrument maker. In 1845, William formed a partnership with Jonas Phelps under the firm name of Phelps & Gurley.

, worked for Oscar Hanks, a surveying instrument maker in Troy, New York, and then went into partnership with Jonas H. Phelps, another local instrument maker. Lewis Ephraim Gurley (1826–1897) worked for Phelps & Gurley, earned a B.A. from Union College

in Schenectady and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree. He

then rejoined the firm and i

n 1852 the Gurley brothers purchased Jonas Phelps' interest in the business and the firm became known as W. & L. E. Gurley.

W. & L. E. Gurley was soon the largest manufacturer of engineering and surveying instruments in the United States. Several factors contributed to their success. Both men, having earned degrees in civil engineering, appreciated the practical applications of technology, and aimed to set their company at the cutting edge of instrument technology. The Gurleys pioneered in mass marketing as well as mass production of instruments.They established a factory rather than a craft workshop, practiced a strict division of labor, hired workers who were relatively unskilled, advertised widely, and offered instruments at competitive prices. Their Manual of the Principal Instruments Used in American Engineering and Surveying, published from 1855 to 1921, was a catalog of their instruments and an intelligent explanation of how they were to be used.

The design of Gurley instruments remained remarkably stable for many years, making it difficult to determine the date of a particular instrument. But there are some important clues. Since the signatures on the early Gurley instruments were cut by hand, the letters have V-shaped trenches, and their lines are of varying width. By contrast, the signatures on Gurley instruments made after 1876 were done with an engraving machine, and thus have lines with vertical walls and uniform width.

Th

e finish on Gurley instruments is not a good dating characteristic, but may serve as a guide. Since 1855, and probably before, the customer had the option of either a "bright" finish of lacquered brass, or a "bronze" finish, achieved by acid treatment of the polished surfaces before lacquering. Until the mid 1870s, unless otherwise specified, all instruments were furnished "bright." From that time until about 1900 compasses were furnished "bright," and transits, levels, and solar instruments were "bronzed." Aluminum instruments, first offered in 1876 but not ostensibly marketed until about 1895, were always furnished with a "natural" finish. The "morocco" finish was introduced in 1916. In 1886 Gurley made a basic design modification to its transits. The two most obvious changes were the introduction of spring opposed tangent screws, and the replacement of the straight legged "A" form telescope supports with a bent leg design.

The Gurleys introduced serial numbers in 1908, with the first digits indicating the year of manufacture, and the latter digits indicating production rate. Thus, transit #9296 was the 296th Gurley instrument made in 1909.

W. & L. E. Gurley was incorporated in 1900, with all the stock held by the family. Teledyne purchased the firm in 1968, began trading as Teledyne-Gurley, and phased out the production of surveying instruments soon thereafter.

Although Gurley was neither the inventor nor the earliest producer of solar instruments, when it finally got into the game it became a major player. The completeness of their line, the diversity of their designs, and the sheer numbers made, justify a study of Gurley's solar instruments. The Gurleys introduced three solar instruments in 1858. Burt's solar compass.

Gurley's original Solar Compass was similar to Burt's improved solar compass. A second form, in which the tangent screws were moved close to their arcs, was introduced in the 1860s. A third form, with modified declination are, was introduced in 1895. The fourth and final design appeared in 1911, and was discontinued in 1915. This form incorporated redesigned declination and latitude arcs, and the solar apparatus was mounted over a full compass. Gurley's Solar and Rail Road Compass was a transitional piece, introduced in 1858 and retired in the 1860s. This was a conversion of Gurley's standard Rail Road Compass in which the brass ring, glass cover, magnetic needle, and center pin were replaced with the solar apparatus mounted on a circular brass plate.

Gurley's Solar Telescope Compass introduced in 1858 consisted of a solar apparatus mounted on a circular brass plate to which was affixed a telescopic sight. A second form, with the tangent screws moved close to their arcs as in the Solar Compass, was introduced in the 1860s. This instrument was not successful--"the position of the telescope to one side of the center, and the excess weight on that side have always been serious objections to its use in the field"--and Gurley sold

Gurley's Solar Telescope

their last one in 1870. Gurley also produced a line of pocket compasses that mirrored their full scale line. These smaller instruments could be used on a tripod or jacobs staff, and could even be provided with leveling heads and telescopic sights. Establishing the date of these instruments is particularly difficult, because Gurley never put serial numbers on them.

By the mid 19th century the transit had become standard for topographic surveys and, in terms of sales, was probably the most important instrument. It was imperative that a solar transit be devised. By the late 1860s the rush was 0 11. The first solar transit was invented by William Schmolz, a San Francisco instrument maker patented by him on December 24, 1867. His solar consisted of an attachment, basically of Burt's 1850 configuration, mounted on top of the transit telescope at the axis. Schmolz's invention was quickly followed by F. R. Seibert's solar transit in 1869, Benjamin Lyman's solar compass patented in 187 I, Harrison Pearson's solar attachment patented in 1875, Buff & Berger's Pearson's solar attachment in 1878, and J. W. Holmes' solar theodolite also in 1878.

The Gurleys could not afford to be left out of the market in such a vital area.

In

mid-1874 William Gurley sent his brother-inlaw, attorney Charles A. Kenney, to visit William Schmolz and to negotiate the purchase of his patent. On August 10, 1874 Schmolz agreed to sell the rights to Kenney for ,000 in gold coin. On October 14, 1874 the patent for "Improvements in Solar and Transit Instrument" was transferred to Kenney, and from Kenney to W. & L.E. Gurley, with one provision: "But I, the said Schmolz, hereby reserve to myself the privilege of manufacturing at my shop in said San Francisco, and using the said improvement on one of said instruments and no more, in each and every year hereafter."

Production of the Solar Attachments--which were always referred to as the Burt Solar Attachment began right away. 8 solar attachments were mounted onto Engineers' Transits with either 4" or 5" needles, and onto Surveyors' Transits with either 5" or 5 1/2" needles. In addition, older instruments could sent to the factory to be retrofitted with the new device. The solar attachment was particularly useful on the Light Mountain Transit introduced in 1876. In fact, of the approximately 500 Light Mountain Transits made from 1876 to 1885, nearly 40% were solar. During that same period, approximately 70% of all solar transits made were Light Mountain Solar Transits.

The Solar attachments continued in production with only minor modifications until 1948. The original design had no cross support. The 1876 design includes an arcuate cross support. The 1883 version has a straight cross support.

In

the 1911-12 form the cross support is aligned with the spindle.

W. & L.E. Gurley patented a Latitude Level on September 2, 1884. Its purpose was to "recover the Latitude of a Solar Transit, without referring to the vertical arc; and generally for setting the telescope at any desired angle in running grades, etc." By 1885 this device had been redesigned to include two adjustment screws instead of one. The Latitude Level was first offered in 1885, and was furnished, at no charge, on all solar transits made thereafter.

The R. M. Jones Latitude Arc was Patented on January 16, 1883. Gurley secured exclusive rights to its manufacture, and it first appeared in their 1884

Manual.

This device had its own vertical arc and latitude level, and replaced the normal corresponding equipment.